So, I’ve Decided to Write a Blog…!

Partly to share what I’ve learned with others, but mostly to serve as a way to document my explorations in weaving and art. I hope you find it interesting and maybe even useful! And for those of you non-weavers, I apologize in advance for all the strange words, but hope it is still somewhat interesting to you!

Lately I’ve been exploring a weave that creates curves by weaving some sections in plain weave and leaving other sections as long floats. Grouped Weft Distortions is the term used by Jan Shenton in Woven Textile Design and she defines it as such:

“The weave construction is based on alternating blocks of plain weave woven alongside blocks of floating warp ends in a chequerboard pattern. The undulating lines are formed by the opposing densely woven structure sitting alongside a loosely woven structure, with the tightly woven ends and picks naturally moving into the loosely woven areas.”

I love the idea of undulating lines and wanted to explore this pattern more for potential use in some of my wall pieces. I believe that Honeycomb, a commonly used weaving term, falls in this category, but I will use Grouped Weft as my description for clarity’s sake.

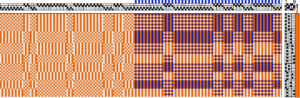

The most common threading plan for this weave is a block weave, and is based on two blocks, or sections, of plain weave. But it can also be designed with more than two blocks, and woven as twill instead of plain weave, depending on how many shafts you have available.

For my explorations, I started out using a two-block, plain weave threading.

Block A = shafts 1 & 2 . Block B = shafts 3 & 4 . Each block can be repeated in the warp threading as many times as needed to make various length sections.

Treadling is such that while one block is being woven in plain weave, the ends, or warp threads, of the other block are held open – alternating ends in a continuous open shed so that the weft yarns are trapped between the two sets of warp ends and can float freely. In other words, while the weft is weaving block A in plain weave, the odd ends of block B are being lifted with each pass of the weft so that all weft passes will gather together between the odd ends and the even ends of block B.

This weave is similar to Honeycomb, except that the weft floats are trapped between the floating warp ends. Like Honeycomb, however, a thicker or textured yarn can be used in two plain weave passes between the weft blocks. If woven somewhat loosely, and after wet finishing, they will curve around the plain weave blocks and move into the float blocks forming the undulating curves that give Honeycomb its name.

For the first warp I used 10/2 cotton sett at 24epi. Half of the warp I alternated light and dark yarn. The other half was all light colored yarn. I wanted to see how the half with dark and light would play out when lifting alternating ends for the float sections.

The draft below shows two blocks in the threading – block A (shafts 1 & 2) and block B (shafts 3 & 4). When I wove block A in plain weave and also lifted shaft 3 with each pick, all the dark warp yarns would lift to cover the floating wefts. Likewise, when I wove block A in plain weave and lifted shaft 4 every time, all the light yarns would show. I created treadlings for all the combinations which I could use in my sampling.

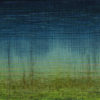

I regret not getting any pictures of this warp on the loom, but here are some pictures of the samples after wet finishing. It was interesting, but not unexpected, to see the color and weave patterns in the plain weave cells of the alternated warp.

Above: wefts – 10/2 grey cotton with a thick red wool outline; 20/2 orange cotton. Note that sometimes the white warp ends are floating and sometimes the dark ends are floating on the right side of this piece.

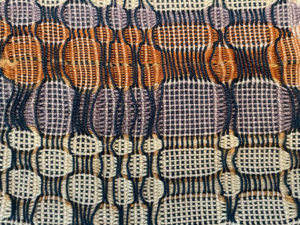

I cut off this sample because I wanted to resley the warp from 24epi to 20epi to see what kind of difference that would make. Here are some pictures of the sample at 20epi. It was definitely a looser, more drapey fabric and allowed finer wefts to pack down more and create more of a weft-faced appearance in the plain weave cells.

Above: wefts – 10/2 cotton with heavy raffia outlines; red fine wool, doubled, with leather-like cording outlines; black fine wool with yarn made from handspun sewing pattern paper as the outlines. Notice how the raffia buckles and kinks as it forced to move around the woven cells.

I also experimented with beating the weft with varying degrees of firmness. Below shows the progression of beating 60/2 silk hard (top) to softer (bottom).

There was also the question of how wide to make the blocks and how long to treadle each block. The picture below shows a variety of sizes of widths and length of plain weave cells and the floating cells adjacent to them. I think that the narrower blocks (6 ends wide) were a little too narrow and got lost among the warp floats. I did like the way the long warp floats wavered back and forth when I treadled a block for more that ½”.

Overall, I learned that although 20epi give me a nice drapey fabric, I appreciated the firmness and stiffness of the 24epi as it would apply to a wall hanging. I also realized that I like to outline the cells with a thicker yarn but it can be overwhelming if used too much.

Thank you for reading!

Next time, Grouped Weft on a painted warp using three blocks!